Today, the fact that human activities lead to global warming is no longer a subject: the increase in the frequency of extreme climatic phenomena (heat waves, El Niño) or the covid pandemic over the past two years are good examples. One of the mechanisms for mitigating global warming consists of making a carbon contribution, through the purchase of carbon credits. It is commonly accepted that the acquisition of such credits can be done by planting trees. However, forests are not the source with the greatest potential for carbon sequestration: 55% of the CO2 captured by photosynthesis each year in the world is captured by the oceans. The conservation and restoration of the oceans are therefore essential to maintain acceptable living conditions on our planet.

By Pierre-Emmanuel GUILHEMSANS-VENDÉ, R&D Consultant at TNP Consultants.

A very slow realization

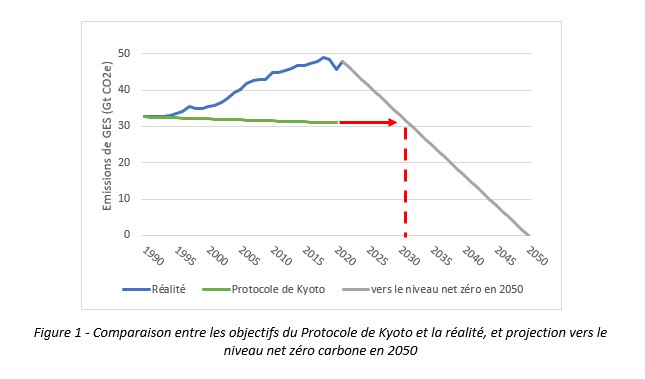

Since March 21, 1994, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has officially recognized the existence of climate change and human responsibility for this phenomenon. This convention has since been ratified by 195 countries, called “Parties”. In 1995, an annual meeting of signatory States to the UNFCCC was created: the Conference of Parties (COP). In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol, aimed at reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, was signed at COP 3. GHG emissions must be reduced by 5.2% by 2020, with 1990 as the year benchmark (for the EU, 8%). The EU did reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 23% between 1990 and 2018 and therefore exceeded its target… but at the global level, emissions have increased by 67%. Thus, if theoretically the phenomenon is recognized, in reality awareness is slow and, despite all the mechanisms put in place to mitigate global warming, emissions have never stopped increasing (see Figure 1).

In 2015, during COP 21, the Paris agreements were signed. They aim to limit global warming to below 2°C, preferably 1.5°C. The objective of a net zero level by 2050 is displayed, i.e. a net balance of zero emissions. Why limit the increase to 2°C, or even 1.5°C? There are multiple reasons for this question, such as limiting the rise in water levels, the collapse of biodiversity, extreme climatic phenomena… and more pragmatically, +2°C is equivalent to a drop of 0.2 to 2 % of global income each year according to the 2014 IPCC report. In 2006, Nicholas Stern had already warned that the cost of inaction against global warming would cost 5 to 20% of global GDP against only 1% for that of the action !

We must therefore reduce our emissions drastically and even ensure that we are at net zero by 2050 in order to hope to limit global warming to below 2°C. We can also note that the reduction in emissions to be agreed by 2030 corresponds to the global objective of the Kyoto Protocol: we must achieve in 10 years what could not be done in 30 years (with a reduction corresponding to the total decline over 30 years)! In other words, the objective is very ambitious!

What are the mechanisms for mitigating global warming?

But then what are the existing solutions that would allow us to achieve this objective?

To respond to the problem, there are currently 3 global mechanisms for reducing CO2 emissions:

1. Carbon markets

Two types of carbon markets: compliance markets (ETS) and voluntary markets. Fit for 55 plans to include maritime (3.3%) and road transport (17%) and building (14%) in the ETS from 2025, which would increase the percentage of EU emissions covered by the ETS from around 45% to 75%.

2. National or multinational regulations/initiatives, outside ETS

For example, within the EU, GHG reduction targets are effectively set for the sectors covered by the ETS but also for sectors outside the ETS.

| Energy climate package 2021-2030 (2014) | Fit for 55 package (2021) | |

| GHG emissions from 1990 to 2030 | – 40 % | – 55 % |

| Share of renewable energies in 2030 | 27 % | 40 % |

| Primary energy consumption | -27 % | – 40 % |

| GHG emissions from ETS sectors from 2005 to 2030 | -43 % | – 61 % |

| GHG emissions from non-ETS sectors from 2005 to 2030 | – 30 % | – 40 % |

3. Green bonds

It is a bond loan issued on the financial markets, by a company or a public entity to finance sustainable development projects. For example, the SNCF issues green bonds to finance the purchase of new trains or the maintenance of existing trains, the train being 30 times less polluting than the car (60 times for the plane).

Among these 3 mechanisms, we will focus more particularly on carbon markets, and more specifically on voluntary markets. Compliance markets will be discussed in another article.

Voluntary markets, contribution lever accessible to all

The first voluntary markets date from 1996, following the second IPCC report, but they really took off only in 2006, with the creation of voluntary labels.

The objective of voluntary markets is to reduce GHG emissions by offering an alternative to compliance markets, access to which is restricted to a limited number of players. This is based on a voluntary approach: there is no obligation and it is accessible to everyone. Only one mechanism is used: the funding of contribution projects.

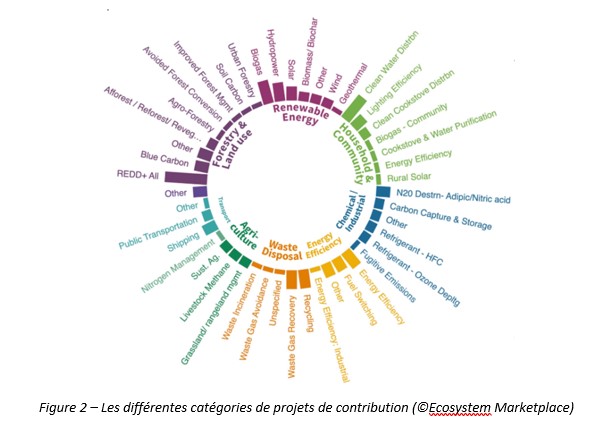

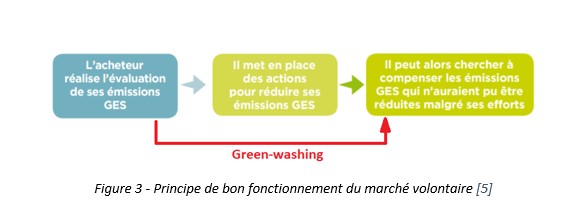

These projects can reduce GHG emissions (more efficient and/or low-carbon technology, such as hydrogen buses) or sequester: for example, planting trees, using CO2 as a refrigerant or burial in the ground. We can find all the categories of contribution projects in Figure 2. But, before being able to make a contribution and in order to best respect the ERC principle (Avoid, Reduce, Compensate), the buyer must first carry out a carbon assessment of its GHG emissions and implement actions to reduce its GHG emissions. Only then will he be legitimate in his contribution process: otherwise, this is called greenwashing (see Figure 3).

The voluntary market, with more than 3,600 projects since its inception, continues to grow, especially over the past 3 years. In 2021, the annual market value exceeds €1 billion for the first time in its history and even peaks at €1.985 billion. It is necessary to remwWonter to 2008 to have the 2nd largest capitalization, 2020 being only 3rd. The cumulative size and value of the market from its beginnings until the end of 2021 are 1.982 Gt of avoided GHG emissions and €8 billion, according to Ecosystem Marketplace, a quarter having been achieved in 2021 alone.

In these carbon contribution projects, the unit used is the carbon credit: one credit corresponds to 1 t of CO2 equivalent. The average price of carbon credits is €4 in 2021, i.e. 60% more than in 2020. This trend towards inflation of the voluntary market will most likely continue, even increase since it is expected that by 2025, demand exceeds supply. The most popular projects are related to forestry activities and land use (see Figure 2), corresponding to more than 46% of the volumes traded and 67% of the market value in 2021. However, energy projects renewables have been growing strongly since 2019, with equivalent or even higher volumes, and prices increasing sharply – +109% from 2020 to 2021 –, where those of forestry activities have changed little: +7% from 2020 to 2021. The majority of projects (65% in 2021) correspond to reforestation, restoration or safeguarding of forests: we can speak here of green carbon credits. These carbon credits are sold, according to Ecosystem Marketplace, at around €5.80 each. As an individual, this type of carbon credit is easily accessible via several online platforms such as EcoTree, Olive Gaea, Coforest, MyTree or even 8 billion trees, at prices that are nevertheless significantly higher and variable (1.67 to 36 € per tree and €11 to €36 per credit, depending on the tree species, its geolocation and whether it lives for 20 years or 1 century and beyond).

Blue carbon credits, a market to be developed

The voluntary market, with more than 3,600 projects since its inception, continues to grow, especially over the past 3 years. In 2021, the annual market value exceeds €1 billion for the first time in its history and even peaks at €1.985 billion. It is necessary to remwWonter to 2008 to have the 2nd largest capitalization, 2020 being only 3rd. The cumulative size and value of the market from its inception until the end of 2021 are 1.982 Gt of avoided GHG emissions and €8 billion, according to Ecosystem Marketplace, a quarter having been achieved in 2021 alone.

In these carbon contribution projects, the unit used is the carbon credit: one credit corresponds to 1 t of CO2 equivalent. The average price of carbon credits is €4 in 2021, i.e. 60% more than in 2020. This trend towards inflation of the voluntary market will most likely continue, even increase since it is expected that by 2025, demand exceeds supply. The most popular projects are related to forestry activities and land use (see Figure 2), corresponding to more than 46% of the volumes traded and 67% of the market value in 2021. However, energy projects renewables have been growing strongly since 2019, with equivalent or even higher volumes, and prices increasing sharply – +109% from 2020 to 2021 –, where those of forestry activities have changed little: +7% from 2020 to 2021. The majority of projects (65% in 2021) correspond to reforestation, restoration or safeguarding of forests: we can speak here of green carbon credits. These carbon credits are sold, according to Ecosystem Marketplace, at around €5.80 each. As an individual, this type of carbon credit is easily accessible via several online platforms such as EcoTree, Olive Gaea, Coforest, MyTree or even 8 billion trees, at prices that are nevertheless significantly higher and variable (1.67 to 36 € per tree and €11 to €36 per credit, depending on the tree species, its geolocation and whether it lives for 20 years or 1 century and beyond).

Blue carbon credits, a market to be developed

Green carbon credits are thus what is most developed and best known to the general public about the carbon contribution, and often synonymous with greenwashing. However, they are not the source with the greatest potential for carrying out carbon sequestration: 55% of the CO2 captured by photosynthesis each year in the world is captured by the oceans, hence the name blue carbon. In addition, coastal ecosystems (mangroves, seagrass beds and coastal marshes), while covering only 0.2% of the world’s ocean surface, alone store 46.9% of this blue carbon in ocean sediments. These ecosystems have a carbon sequestration rate 30 to 50 times greater than that of forests. Nevertheless, at present, blue carbon is underexploited with only a few projects stemming from the protection of mangroves.

It is in this context that the start-up BlueLeaf Conservation (BLC), founded by Lionel POURCHIER and Frédéric FAVRE and partner of TNP since April 2022, intervenes. BLC is currently developing a pilot project to monitor Posidonia seagrass beds in the bay of Cannes in collaboration with the NGO Nature Dive (this NGO plants Posidonia seagrass beds and participates in raising awareness and education on the subject), the Collectivité of Cannes, the city of Cannes and the Cannes Foundation. The idea is to be able to determine a model linking hectares of Posidonia with tons of CO2 and to approve this methodology via the low carbon label. Between 0 and 15 m, the monitoring of the meadows can be done via satellites (beyond, between 15 and 40 m, problem of luminosity). In addition, there is a scientific lock on the development of a generalizable satellite recognition tool (depending on the coast studied, there will be a multifactorial variation of the image to be analyzed). The methodology approved via the low-carbon label could give rise to the issuance of carbon credits, consisting of 80% of the protection of the existing and 20% of restoration.

It is thus necessary to mobilize and federate the stakeholders to ensure the financing of projects for the conservation and restoration of marine ecosystems. Private companies but also the Green Climate Funds, international donors, States and local authorities are these potential stakeholders. At the moment, organizations and governments are reluctant to commit to funding marine conservation projects in the absence of a clear and proven carbon footprint methodology. In addition, there is no consensus on a single voluntary label that would lower certification costs by volume effect, and therefore lower the cost of blue carbon credits and make them more attractive. Lionel POURCHIER proposes the creation.

Sources

“Fit for 55”: a new cycle of European climate policies”, RPUE – Permanent Representation of France to the European Union, 15 July 2021.

IPCC, “Climate Change: Synthesis Report”, 2014.

[ N. Stern, “The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review”, Oct. 2006.

“Fit for 55: the European Commission is reviewing its entire climate policy in the light of its new ambition for 2030”, Citepa, July 15, 2021.

ADEME, “Voluntary compensation: approaches and limits”, June 2012.

“Carbon Credit Projects & Transactions”, Trove Intelligence. https://trove-intelligence.com

Ecosystem MarketPlace Insights Brief, “The Art of Integrity: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2022 Q3,” August 2022.

C. M. Duarte et al., “The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation”, Nature Climate Change, October 29, 2013.

L. Pourchier and F. Favre, “Blue Leaf Conservation website”. https://blueleafconservation.com/